The Democratic Party: Fighting for the Little Guy!*

*Definition of "Little Guy" subject to change.

This is the second post in my two-part mini-series tracing the through-lines of America’s major political parties. Last time, I explored the four conservative values that have held the Republican Party together over time. As Republicans have historically been the defenders of the status quo, Democrats have framed themselves as protectors of the oppressed masses — those of whom for which that status quo doesn’t work.

This coalition has contained a broad range of special interest groups, each with its own specific, often incompatible, policy demands. Importantly, which groups get included in that definition of “oppressed” has also changed dramatically over time and, as you might have guessed, has not always been accurate to reality.

For that reason, I selected four Democratic presidential nominees (not necessarily general election winners!) that I think best exemplify that shifting definition. While other politicians may have been more popular, or are better-known today, these campaigns represented specific changes in the types of voters that comprised the Democratic Party.

Andrew Jackson (1824, 1828, 1832)

No better place to start than the beginning! General Andrew Jackson was the founder of the Democratic Party. Originally from the backwoods of the Carolinas, and an orphan at 14,1 he became a prominent lawyer and planter in the then-frontier town of Nashville. He gained national fame for his daring defense of New Orleans during the War of 1812. His humble background earned him credibility with the poor farmers of the South and (Mid)West. Though he was known for his quick temper, he often used it to intimidate his opponents.

This is an era I have discussed at length due to its similarities to today’s ideological divides. Put simply, Jackson’s political rise was the result of deep distrust in the establishment following the economic Panic of 1819. He also benefited from the expansion of voting rights (for White males), such as the elimination of property requirements and the selection of presidential electors by popular vote (as opposed to state legislatures).2

In the 1824 presidential election, Jackson won the popular vote but not the electoral college, sending the decision to the House of Representatives. They instead chose nepo-baby John Quincy Adams, fueling accusations of corruption by Jackson supporters. They immediately began campaigning for an 1828 rematch, forming the basis of the Democratic Party.

Jackson easily defeated Adams in the next election. As president, he used his authority to bend the government to his will, dismantling the National Bank and appointing party loyalists to federal jobs. He also defended states’ rights to encroach on Native American land, an issue hugely important to his supporters in the frontier. Jackson and his successors used the Indian Removal Act to forcibly relocate tribes farther west. The Democrats’ embrace of territorial expansion, primarily for plantation owners, linked the party to the interests of slave-owners, and eventually, southern sectional politics as a whole.

William Jennings Bryan (1896, 1900, 1908)

After losing the Civil War, the Democratic Party unsurprisingly struggled to compete at the national level. Their most successful strategy was to run reform-minded northerners who were critical of rampant political corruption in big cities. This culminated in the election of Grover Cleveland, the party’s first presidential winner in nearly 30 years. I previously argued that Cleveland’s two nonconsecutive terms were the result of a hollow and unhealthy party, one that was ripe for a major realignment.

Cleveland was a devout economic conservative. When the Panic of 1893 caused a run on gold reserves, farmers in the West demanded the coinage of silver to ease their debt burden. Cleveland refused and doubled-down on the Gold Standard, sending the economy deeper into a depression. At the 1896 Democratic National Convention, Free Silver supporters revolted against the President’s policies.

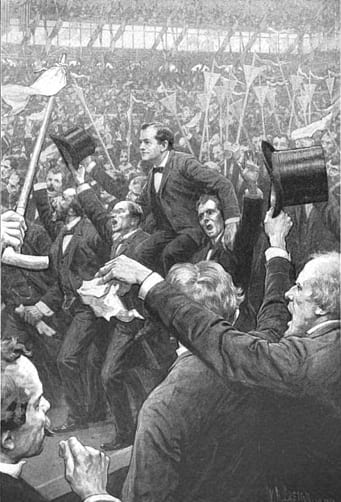

The event’s most memorable speech was delivered by Nebraska Representative William Jennings Bryan. He borrowed upon his Christian faith to warn conservatives, “You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns; you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.” The Cross of Gold speech lifted Bryan into the national conversation and he was selected by the convention to be the party’s next presidential nominee.3

Bryan faced Republican William McKinley in the general election. McKinley appealed directly to business owners startled by Bryan’s economic policies.4 He raised a record-setting amount of money, setting new standards for presidential campaigns. Bryan’s populist base was no match for the Republican Party machine. Though he lost the 1896 election, as well as his subsequent attempts in 1900 and 1908, Bryan transformed the Democratic Party into a coalition that demanded a more active federal government, setting the stage for future progressive presidents.

Franklin D. Roosevelt (1932, 1936, 1940, 1944)

If Bryan refocused the Democratic Party’s priorities, it was Franklin D. Roosevelt who turned them into a winning coalition.

On paper, it seemed like Republican President Herbert Hoover was the perfect person to lead America through the Great Depression, having organized international food relief efforts during World War I. However, much like his predecessors above, he relied on inadequate, conservative economic policies in an attempt to stabilize the market. This time, it was high tariffs on imports that worsened the crisis.

Roosevelt was a rich kid from an elite New York family. But his experience in Democratic politics — not to mention his own personal battle with polio5 — gave him a deep understanding of the Americans’ economic pain. The New Deal, his broad (and somewhat vague) proposal for government relief, attracted multitudes of new voters to the Democratic coalition. They could now count on support from southerners, western famers, urban laborers, immigrants, African Americans, and college-educated professionals. The results were undeniable. Democrats won seven of the next nine presidential elections (famously, four by Roosevelt himself) and dominated in most congressional elections for nearly seventy years.

Of course, there were major ideological contradictions in the New Deal Coalition, too. The inclusion of African Americans into the Democratic Party led to a softening of racial policies at the federal level, such as President Harry Truman’s desegregation of the military. Democratic presidential nominees consequently faced socially conservative third party challengers from the South in the 1948 and 1968 elections — and the party as a whole slowly bled southern support. The New Deal Coalition defined American politics for most of the Twentieth Century, but it couldn’t last forever.

George McGovern (1972)

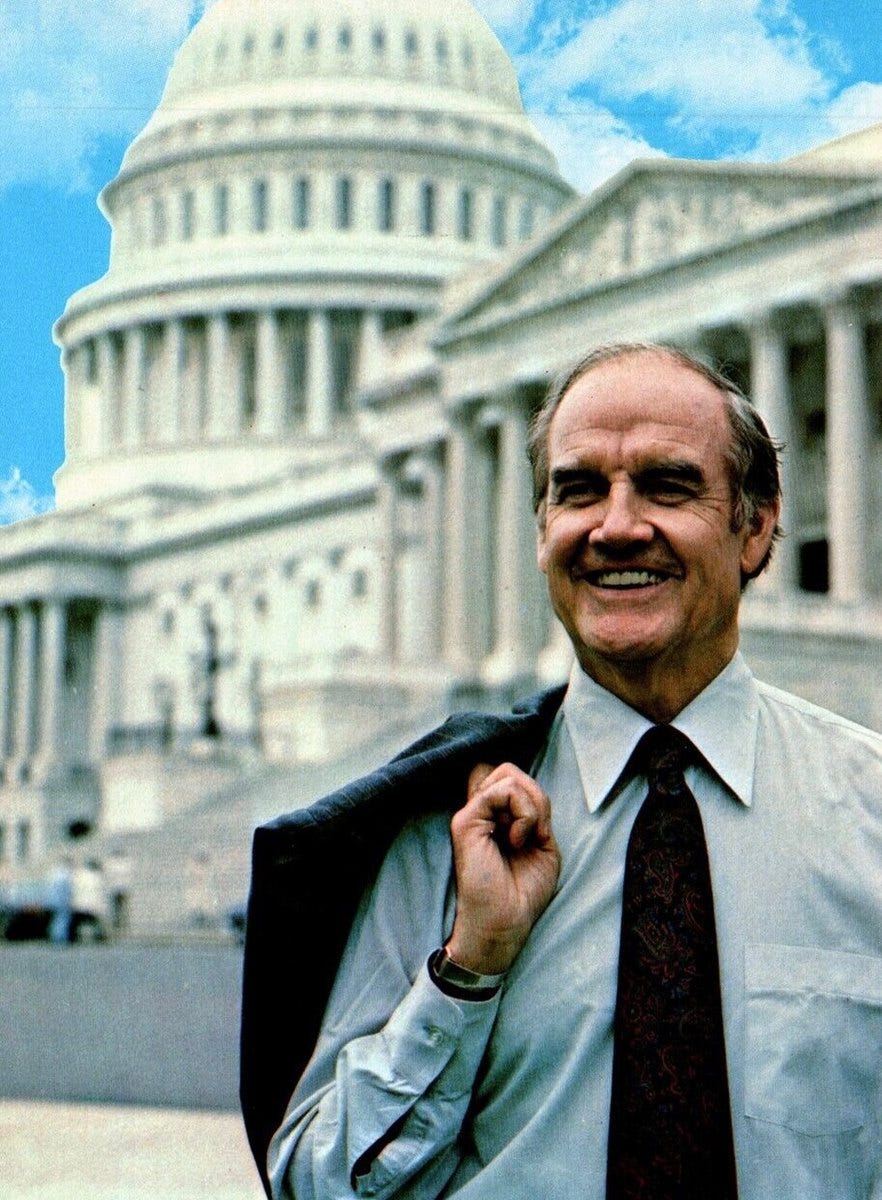

This is my somewhat unorthodox pick. George McGovern’s 1972 presidential campaign might sound obscure from today’s perspective, but it marked an important shift in both party’s coalitions.

The preceding 1968 election had been a disaster for Democrats. The year started with the turn of public perception against President Lyndon B. Johnson and the Vietnam War. To the everyone’s surprise, the President chose not to seek re-election. The party’s next most likely nominee, Robert F. Kennedy, was assassinated by a Palestinian nationalist. At the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, violence broke out between police and anti-war protestors. Vice President Hubert Humphrey won the nomination, but party division and Richard Nixon’s Southern Strategy led to a painful defeat.6

The Democratic Party knew they were out of touch with their base. They responded with a commission, led by South Dakota Senator George McGovern, to implement reforms. The most significant change was to require all states to hold primary elections (or caucuses) to select presidential delegates for the convention — the system we still use today. No longer do party bosses in smoke-filled rooms decide the party’s nominee. Instead, voters have a direct say in the process. This allows grassroots candidates to gain momentum over more established politicians, but it also forces candidates to pander to the party’s most extreme factions (usually before predictably moderating during their general election campaign). Though these changes were first implemented by Democrats, Republicans soon followed suit.

It was no coincidence that the Democrats’ first presidential nominee following the new primary rules was none other than George McGovern himself. His base of highly-engaged anti-war and social justice voters gave him a major advantage. But they also gave moderate voters the impression that the party was being controlled by hippies, playing right into Nixon’s hand. McGovern was crushed in the general election.7

It has been a slow process, but the McGovern campaign cemented the departure of cultural conservatives from the Democratic Party and the end of the New Deal Coalition. Although the primary system has created a more (small-d) democratic process, it has also contributed to increased partisanship on both sides of the aisle.

Liberal Synthesis

I started this series with the acknowledgement that both parties have changed a lot throughout their histories. Democrats, especially, transformed from the party of slavery to the party of Civil Rights. In each era, they presented themselves as the defenders of liberty against the ruling class. Their actual coalitions, however, did not always meet that promise.

Today’s Democrats face another disparity. As they struggle to maintain working class support, many question whether the party still represents the oppressed masses, or is simply a vehicle for the hollow gestures of the educated elite. The answer may come, not from their decision to move left or right ideologically, but from their ability to listen to voters, rather than lecturing them.

Jackson had a rough childhood. His father died in a logging accident before he was born. His eldest brother died of heat stroke while fighting in the American Revolution. Jackson and his remaining brother served as couriers for the Patriots, but were captured by the British. After refusing to polish an officer’s boots, they were struck with a sword. Both caught smallpox before being returned to their mother. Jackson’s brother did not survive. Soon after, his mother contracted cholera and also died. So, I guess it makes sense that Jackson was such an asshole.

By 1832, the only holdout was South Carolina, which reserved this power for the state legislature until Reconstruction.

At 36, Bryan is still the youngest nominee of a major party.

This strategy was the brainchild of his campaign manager, Ohio politician Mark Hanna — notably, Karl Rove’s hero.

Given the rarity of polio in adults, there is some evidence that Roosevelt was actually afflicted with Guillain-Barré Syndrome, an auto-immune disorder.

Nixon won by large margins in the electoral college, but the popular vote was only separated by about 500,000 votes.

Funny enough, this was the election of the Watergate Scandal, wherein Nixon campaign operatives broke into the Democratic headquarters to plant listening devices. Nixon had the election in the bag — they didn’t need to do it!

Really like the through-line you’re drawing. Curious what you make of the present-day Democratic Party though, do they still frame themselves as resisting the ruling class? Since the rise of Trump (though really starting under Obama), it seems like they’ve leaned hard into defending the status quo. Not just in practice, but increasingly in rhetoric too.