The Republican Party: The Four Pillars of Conservatism

A lot has changed in the GOP's 170+ years of existence, but these values have held the party together across leaders, from Abraham Lincoln to Donald Trump.

Both of the major political parties in the United States are pretty old. The Democratic Party was founded in 1828, and the Republicans in 1854. A lot has changed since then! So much so, that we typically regard the parties to have flipped on the ideological spectrum sometime around the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s. But for modern liberals to frame the first Republicans as “on their side” is a mischaracterization.

The Grand Old Party emerged as the successor to the Whigs as the issue of slavery expansion heightened the geographical divide in American politics. I previously argued that Republicans’ success was not based on an adoption of anti-slavery policies, but more broadly, on their embrace of Northern sectional politics and shrewd coalition management. In addition to opposing the South’s cultural advancement, Republicans advocated for an America-first style of social and economic progress that valued stability in the institutions they respected most. Although the specifics of the issues have changed, I see four major through-lines that connect the underlying values of Republicans across political eras.

Defenders of Capitalism

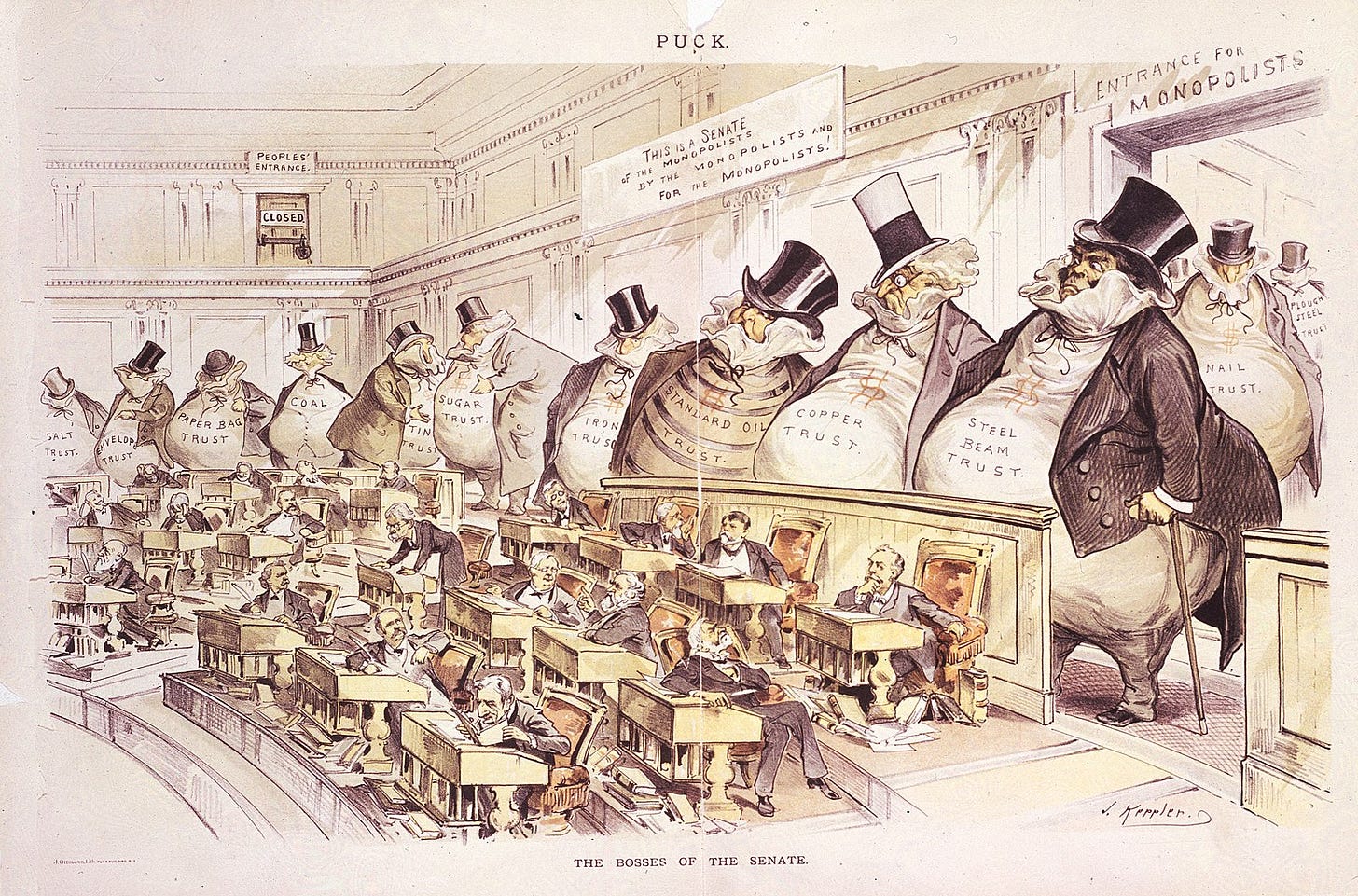

The Civil War was primarily about states’ rights slavery, but it also represented a battle between two competing economic visions for the country. The South was built on an agrarian economy, which required slave labor to be profitable. The North, on the other hand, had industrialized rapidly. Big factories were financed by big banks, creating the foundations of modern Capitalism. Republicans, like the Whigs before them, had a close relationship with business owners. In the Nineteenth Century, this resulted in a platform focused on economic stability through banking regulation, tariffs, and infrastructure investment.

The divide between the owners of capital and common laborers was further entrenched at the outset of the Progressive Era. In the 1896 and 1900 elections, Populist Democrat William Jennings Bryan faced off against Republican William McKinley. Bryan argued for the coinage of silver to ease the debt burden of farmers, while McKinley stood for economic stability through the Gold Standard. Together with his campaign manager, Mark Hanna, McKinley directly appealed to business leaders and raked in a record-breaking amount of political donations — earning him victory in both elections.

McKinley’s successor, Teddy Roosevelt, famously embraced many progressive ideas. However, he ultimately did so in an explicit effort to protect Capitalism from radical socialists. As future Democratic presidents created a more active federal government, Republicans shifted towards the free-market economic conservatism that they are known for today. Although Donald Trump’s tariff policies threaten to overturn that status quo, as of this writing, business leaders seem more willing to adapt to rising manufacturing costs than to risk deeper challenges to capital ownership from the Far Left.

Secure the Border

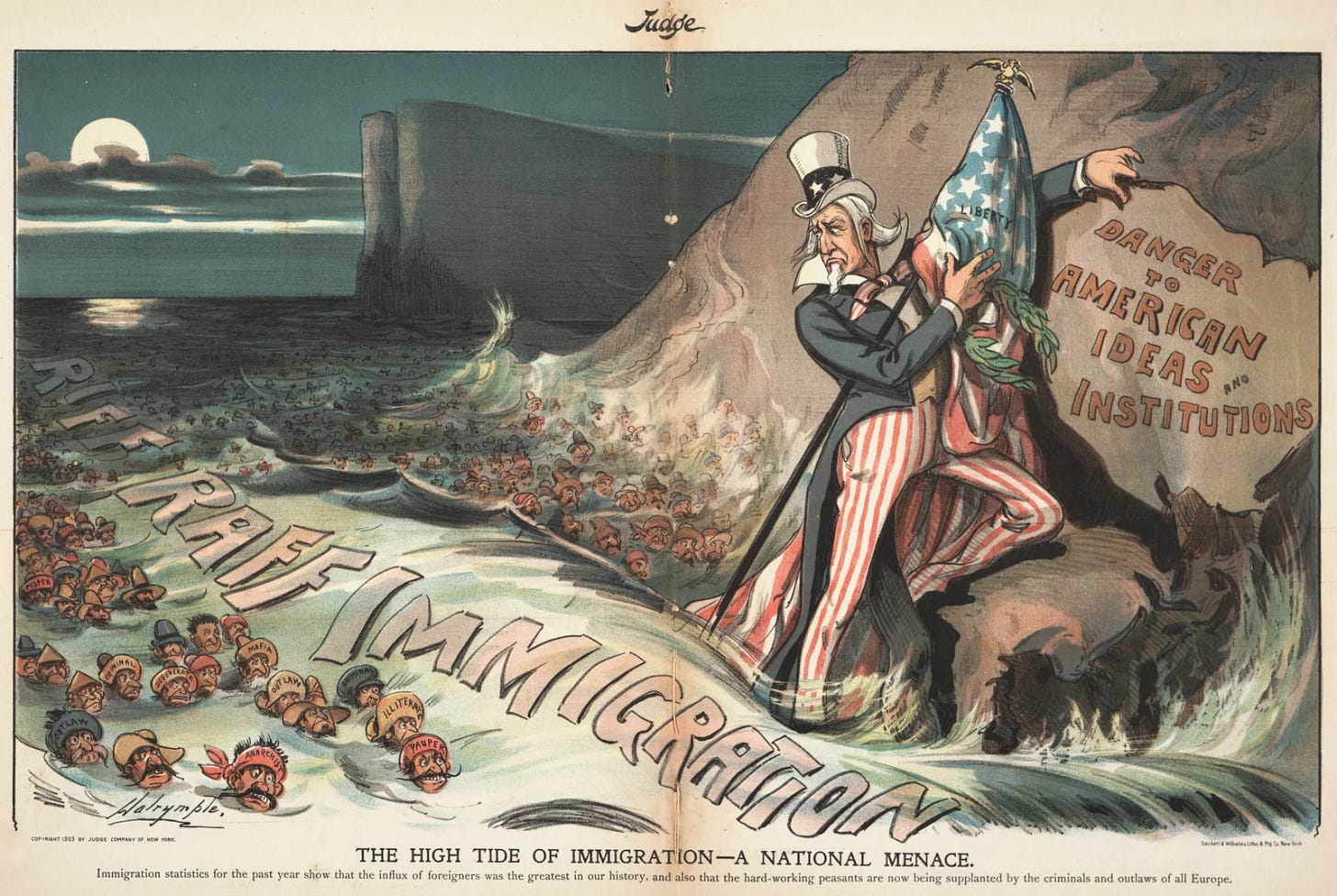

When the Whig Party collapsed in the 1850s, the Republicans weren’t the first major party to form in their wake. The Know Nothings — originally a secret organization whose members were instructed to claim they “knew nothing” about the group’s activities — were a nativist party with growing influence in urban areas. Anti-immigrant sentiment in America was nothing new, but a series of famines in Europe and reduced Transatlantic travel costs led to a surge in new, unskilled immigrants in the 1840s and ‘50s. Most of these immigrants were Catholic, and nativists argued that they did not share the values of true Americans, leading to corruption. However, the Know Nothings’ close association with a single issue, not to mention the selective nature of their membership, limited their potential on the national stage, and they were soon overtaken by the broader Republican coalition. Although party leaders like Abraham Lincoln shied away from this faction, Republicans absorbed many of the same voters who had previously supported the Know Nothings.

Meanwhile, Democratic party machines in cities were savvy to attract new immigrant voters to their side. They offered community support and patronage jobs to immigrants who had few other opportunities. This created political loyalties that lasted generations — culminating in the first Catholic presidential nominee, Al Smith in 1928, and the first Catholic presidential victor, John F. Kennedy in 1960. Of course, the Democratic Party had plenty of nativist voters too, particularly in the South, where the second iteration of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s took on more anti-Catholic and antisemitic rhetoric. But the party was able to maintain its coalition due to mutual distrust of Republicans in both the North and South. Immigrant laborers were an important part of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal Coalition, beginning the slow consolidation of social conservatives into the Republican Party.

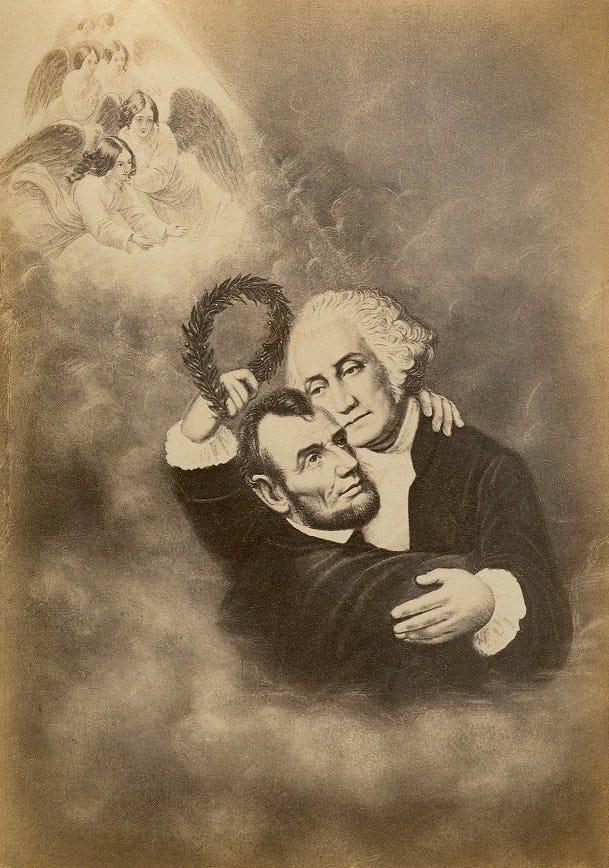

Christian Identity Politics

One thing that I think would surprise most Americans today is that, for much of our country’s history, it was the North, not the South, that was most closely associated with tying Christian morality to political policy. While all Americans were more reliably Christian in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, northern churches typically had larger, more organized congregations. This meant more religious institutions, such as schools, and more activist members. The South, on the other hand, had smaller, more independent churches that placed increased emphasis on personal faith. This motivated their support for small-government policies, the separation of church and state, and protection of individual liberty (for white men).

This dynamic played a key role in debates over slavery. Abolitionists relied heavily on Christian moral arguments in their criticisms of the barbaric institution. It also resulted in Republicans’ adoption of several moral-policing policy positions, including alcohol prohibition, anti-gambling measures, teaching religion in public schools, and enforcing the Sabbath. They earned extra points with Protestant nativists for using these policies to thwart those dastardly Catholic immigrants and their loose morals. As urban areas became increasingly diverse and secular, their relationship to Christian politics changed. Today, of course, Republicans primarily count on rural voters to fill this constituency.

Law & Order

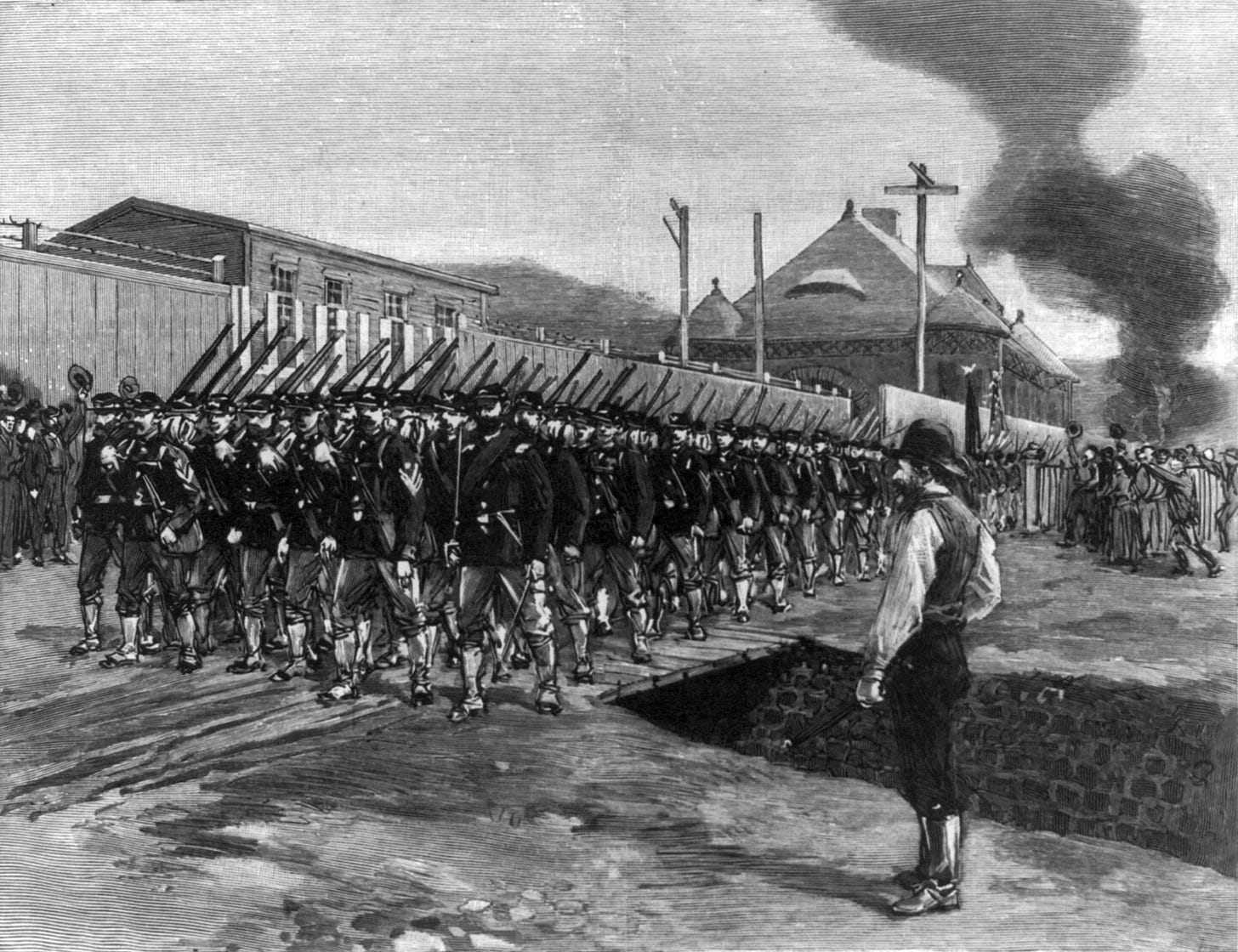

This section serves as a catch-all for the pro-military, pro-police impulse within the Republican Party. Though the specifics may change with the circumstances, Republicans are typically predisposed to respecting those with power and enforcing social stability. Following the Civil War, Republicans obviously had a strong relationship with servicemen and veterans. Soon after, they also became closely associated with the expansion of the American empire overseas. Again, this was best displayed during the McKinley Administration, when Americans’ fervor for battle led to the Spanish-American War — and consequently, the acquisition of the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

A similar tendency is Republicans’ continued opposition to public protests. Early in the labor movement, Republican Presidents Rutherford B. Hayes and Benjamin Harrison made controversial decisions to send federal troops to end union strikes. Both incidents resulted in violence and deaths. Although the political alignment of unions was still nebulous, Hayes and Harrison set a precedent of government intervention on the side of business owners. In the Twentieth Century, Republicans continued their efforts to weaken union influence and similarly opposed social protests during the Civil Rights Era and beyond.

Conservative Synthesis

I’ve written before that Republican voters tend to favor abstract values — Patriotism! Liberty! The Constitution! — over specific policy proposals (in contrast, Democrats have a broad coalition of interest groups, each with a list of demands). Of course, there have been exceptions and hypocrisies to each of the values I outlined above, but they have all represented important factions of the Republican Party throughout its history. An underrated phenomenon of our current political era is that the parties have become more defined by ideology than ever before. The geographic divide between the North and South has weakened, as has demographic indicators such as ancestry. An anti-immigration southerner or a church-going Irish-American have little reason to not vote Republican. Liberals now face new challenges in their efforts to attract voters across the country. In my next post, I’ll explore the through-lines of the Democratic Party, and how they have adapted their belief in individual liberty over time.