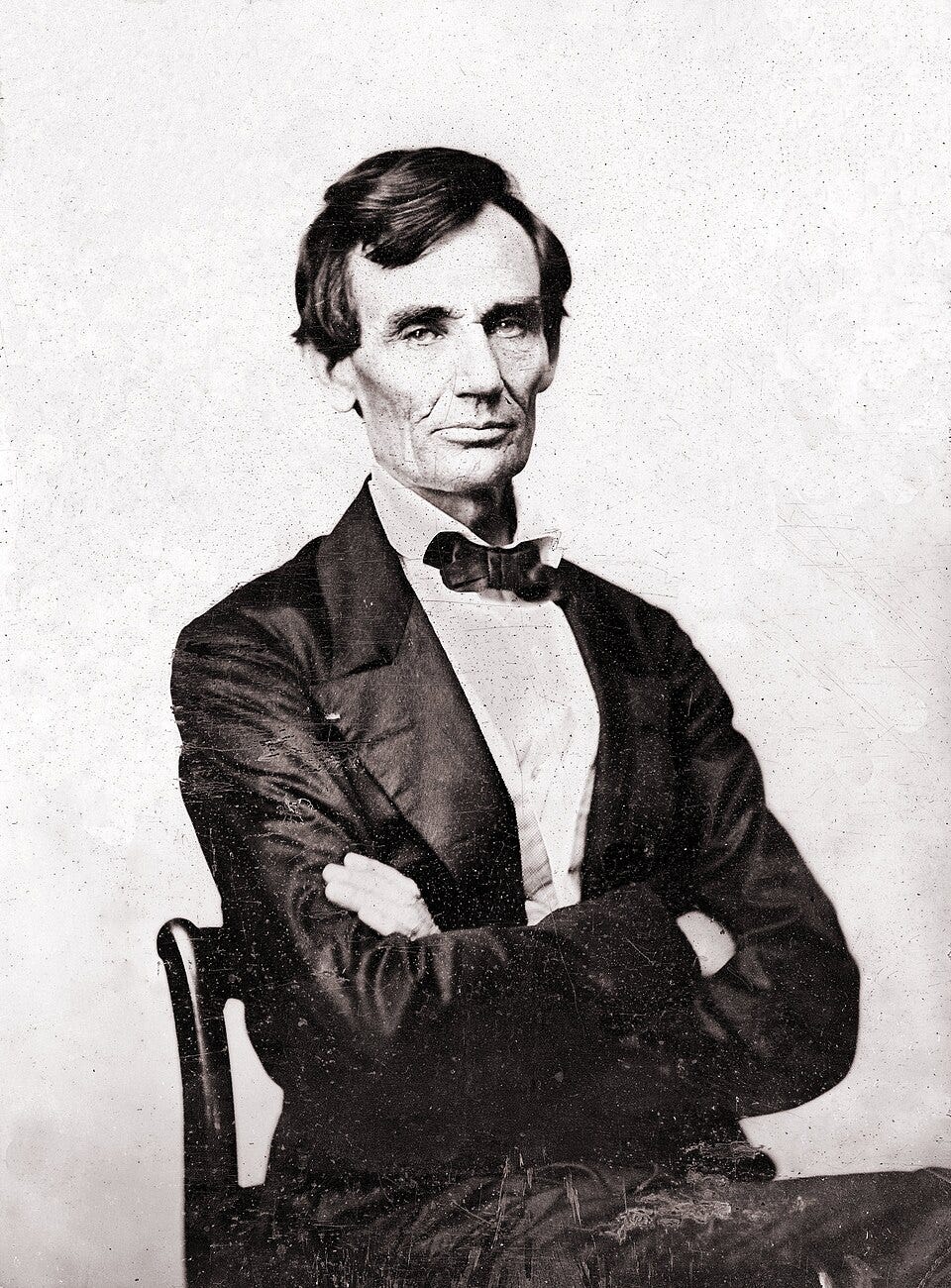

Abraham Lincoln: Whig Party Shill

The preeminent Republican spent most of his life as a Whig loyalist. How should that change our image of America's greatest president?

In 1856, anti-slavery Illinoisans gathered in Bloomington to determine their new political home. In the wake of the Kansas-Nebraska Act,1 Democrats had firmly become the party of the South, and the Whigs ceased to exist altogether. A number of third parties competed for the loyalty of displaced Northerners. The eventual victor was the Republican Party, which combined the pro-industrial economic policies of the Whigs with an embrace of Northern sectional politics.

The most notable speaker at the Bloomington Convention was former Whig Representative Abraham Lincoln. Although the Republican Party, and Lincoln himself at the time, were careful to denounce the expansion of slavery without calling for full abolition, the future president’s speech was a searing takedown of the shameful institution. It was so stirring, in fact, that journalists were supposedly too captivated to actually write it down. Lincoln’s “lost speech,” as it came to be known, was an important part of his journey to the presidency and an illustration of his strong moral principles.

But his embrace of the Republican Party was also a key moment in his political career. Lincoln was a lifelong Whig who regularly put party over ideology. Before he was associated with the grandest ideals of liberty, he was just another party hack. The true story of his political rise should reframe our understanding of what it means to be a successful politician.

Out of the Wilderness

Lincoln’s formative political years aligned closely with the formation of the Whig Party. Its coalition was formed in opposition to Democratic President Andrew Jackson, whose populist rise and abuse of executive authority threatened the stability of the nation. Lincoln was a big fan of the Whigs’ most prominent leader, Kentucky politician Henry Clay. While the party itself was a diverse assortment of Jackson’s enemies, Clay advocated for an innovative economic vision — government spending to promote infrastructure, tariffs to protect domestic manufacturing, and a national bank to regulate the economy.

But Lincoln didn’t just admire Clay’s policy ideas, he molded his self-image around them. The rail-splitter was raised in the Kentucky wilderness, and his adult life — a self-educated lawyer who rarely smoke or drank — was a rejection of that frontier lifestyle. Although his humble beginnings have always been a part of the Lincoln mythology, the man himself rarely referenced his younger days on the campaign trail. Instead, it was the social mobility he earned through personal discipline that he was most proud of. Lincoln was a strong believer in the “right to rise,” the idea that it was the government’s responsibility to create conditions that allowed individuals to improve their circumstances through hard work. To him, the Whig platform of economic advancement was the political realization of those values.

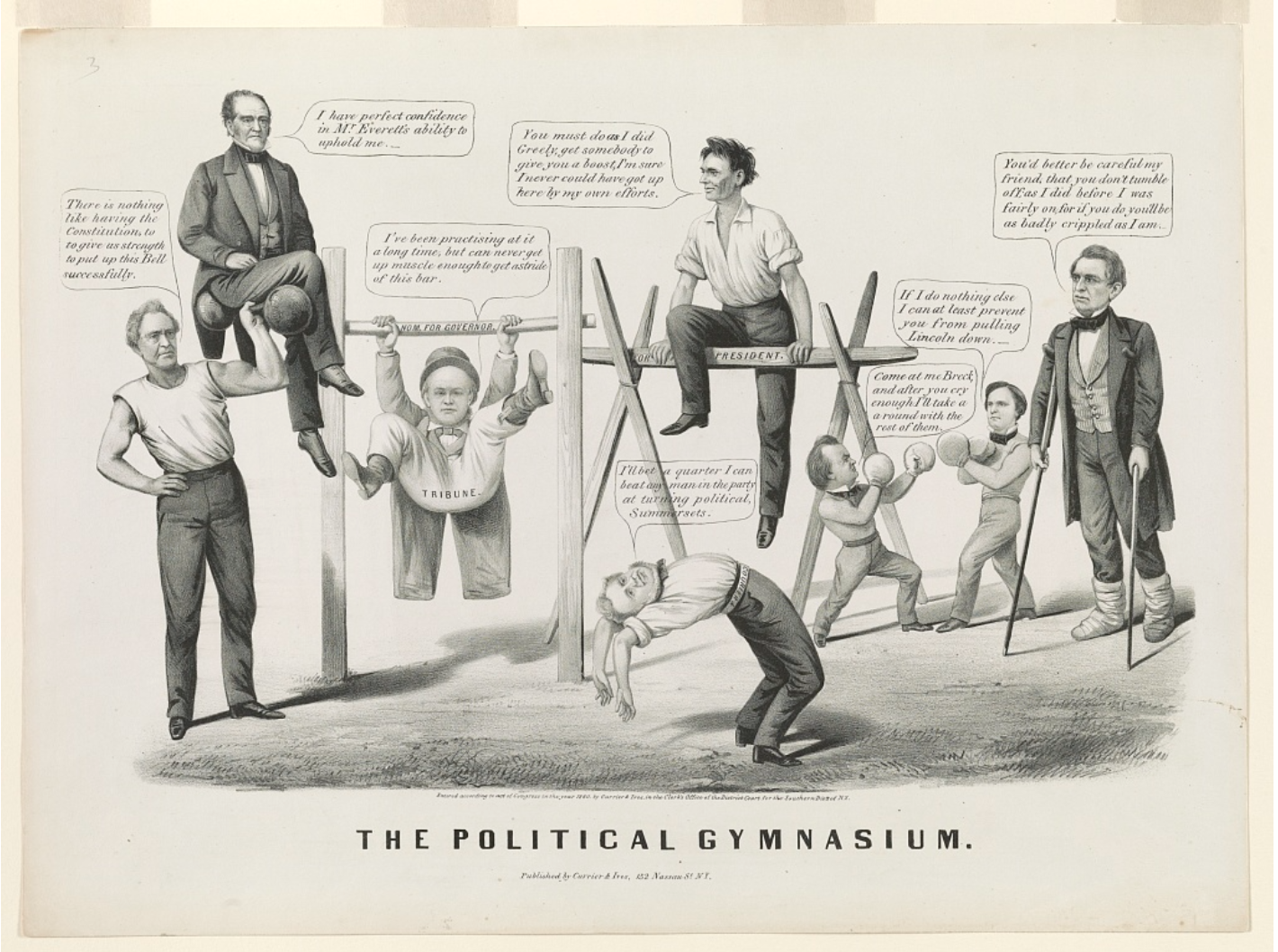

Like today’s political divide, the parties of the 1800s were often associated with particular personality types. Democrats typically valued tradition, while the Whigs promoted progress. Lincoln, of course, embraced progress on a personal and political level. In early speeches, he argued that the Democrats not only stifled the country’s economic advancement with small-government policies, they also encouraged the “passions” of mob rule. This weak-mindedness was a source of tyranny, displayed in vices like alcoholism, and exploited by authoritarians like Jackson. Whigs, on the other hand, represented rationalism, civilized society, and law and order. When Lincoln gave a eulogy for Clay in 1852, it wasn’t the late senator’s economic policies that he celebrated, but rather, his patriotism and self-determination — values that Lincoln identified as key to the prosperity of the nation overall.

The Pragmatic Congressman

Lincoln made political speeches even as a young man and first ran for office at the age of 23, in an unsuccessful bid for the Illinois state house. He ran again two years later as a Whig and won. He served four terms, from 1834-1842. Next, Lincoln served one term in the US House of Representatives. As the only congressional Whig from Illinois, he was best known for his strong opposition for President James K. Polk’s Mexican-American War.

Lincoln was a loyal party member and placed great importance on message unity. In campaign speeches and writings, he displayed strong knowledge of the Whig economic message. He also organized local campaign strategies, outlining the specific duties of party committees and captains in securing Whig votes. He strongly condemned internal division and discouraged third party votes by ideological purists, even in the waning days of the Whig Party. Lincoln’s goal was first and foremost electoral victory.

Lincoln’s political pragmatism was perhaps best displayed by his endorsement of General Zachary Taylor for the 1848 Whig presidential nomination. Taylor’s intra-party opponent was Henry Clay, Lincoln’s hero and a perennial presidential wannabe. But Lincoln was well aware of Clay’s shortcomings. As the party’s ideological leader, he was too divisive for swing voters, and his deal-making on slavery expansion had made him enemies on both sides of the issue. Taylor, on the other hand, was viewed as a blank-slate. He was a life-long military general who had made few ideological commitments. He was a hero of the Mexican-American War, but had been openly critical of President Polk’s leadership. He was a slave-owner, but did not support the expansion of slavery in the newly-acquired Southwest. Lincoln joined six other Whig congressmen, known as the “Young Indians,” to pledge support for Taylor early in the campaign. He knew that, despite his personal admiration of Clay, Taylor had the better chance of victory. Taylor did, in fact, win the nomination and the presidency.

The Last Whig President

At the Bloomington Convention, Lincoln and the other attendees decided to join the Republican Party. But Honest Abe never forgot his Whig roots. As president, he finally made Clay’s economic vision a reality — investing in railroads, promoting public education, instituting tariffs, and modernizing the banking system. In true Whig fashion, he was also cautious of executive authority even during the Civil War. He maintained a close relationship with Congress and was careful to take emergency actions in limited and justified ways. His gradual acceptance of abolition (a powerful personal journey in its own right) was likely key to maintaining his political coalition and achieving the war’s eventual outcome.

But while Lincoln is best known for his moral principles, it was his acceptance of his new political era that set him apart from former Whig leaders. To great statesmen like Clay, organized political parties were black mark on American democracy spurred on by Andrew Jackson. They viewed real governance as the compromises formulated in Congress. Lincoln’s generation, however, understood parties as a necessary consequence of coalition management. Electoral victory meant message unity and internal compromise, often achieved through patronage — the practice of rewarding loyal party supporters with government jobs. Although this system soon became inundated with corruption, Lincoln’s use of the party machine made the Republicans a lasting political organization in a way that the Whigs never were.

Enough About the Whigs!

I’ve written a lot about the Whigs lately because I see a lot of similarities between the their situation and modern Democrats. Both are/were primarily coalitional parties in opposition to small-government populists with an authoritarian leader. At times, Abraham Lincoln was a pragmatic moderate and a visionary ideologue. But beyond that, he was a shrewd politician who was unflinchingly honest about the political realities of his era. Great statesmen couldn’t prevent the Civil War, and ideological purity wouldn’t end it. Lincoln’s historical legacy is one of great moral leadership, but it took a lot of dirty work to achieve his goals. Did that make him soulless? Or skillful?

Resources

Howe, Daniel Walker. “Why Abraham Lincoln Was a Whig.” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, 1995.

Silbey, Joel H. “‘Always a Whig in Politics’ The Partisan Life of Abraham Lincoln.” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, 1986.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act allowed residents of new states to vote on the status of slavery, putting an end to the Missouri Compromise. The fact that the bill had been championed by native Senator Stephen Douglas was an added insult for the attendees of the Bloomington Convention.